posted 20th December 2025

Queen Lili'okalahni, Black Nobility of Hawaaii

Queen Liliʻuokalani and the Atomic Re-Alignment of Sovereignty

Queen Liliʻuokalani occupies a singular position in modern world history: not merely as the last reigning monarch of the Hawaiian Kingdom, but as a living embodiment of what occurs when an indigenous, sovereign order collides with the industrial, imperial logic of modernity. Her life and reign represent a moment of profound civilizational misalignment, in which political power was forcibly detached from cultural legitimacy, ancestral continuity, and moral authority.

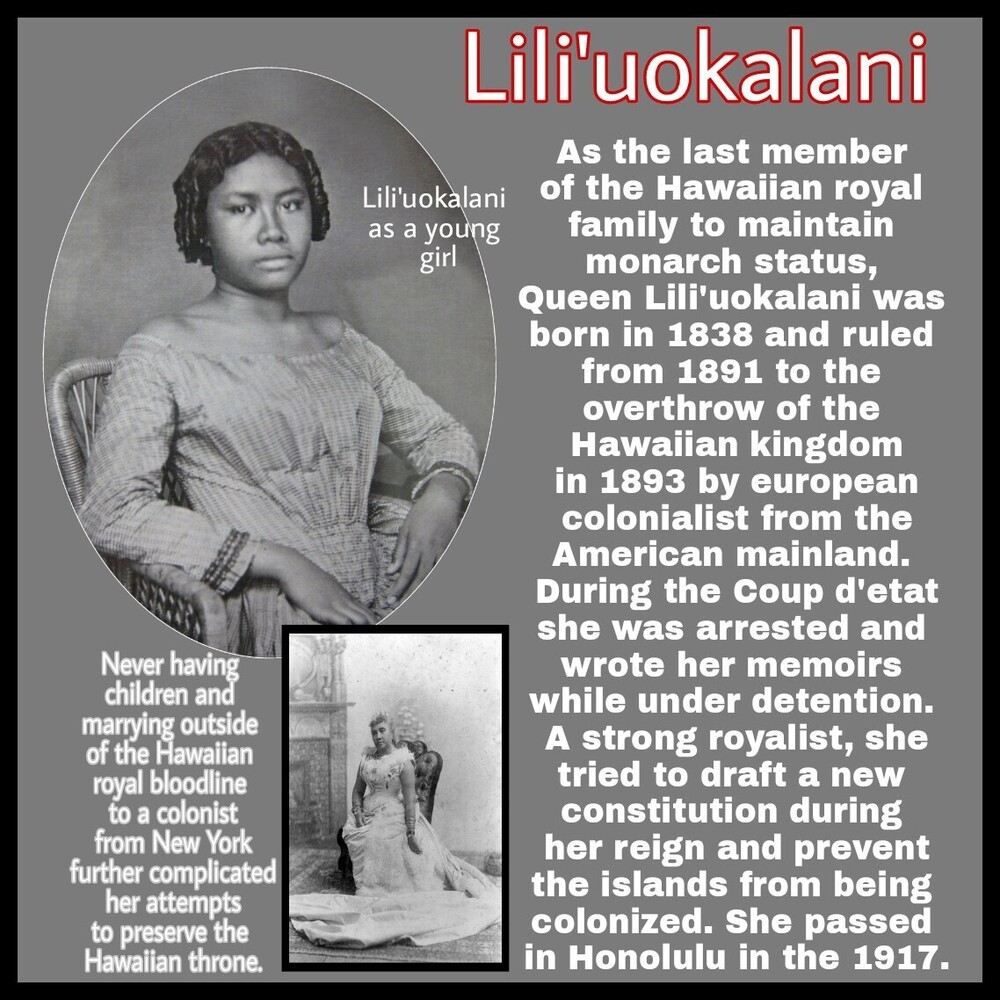

Born Lydia Liliʻu Loloku Walania Kamakaʻeha in 1838, Liliʻuokalani was raised within the aliʻi (nobility) system of Hawaiʻi-an order that fused governance, genealogy, spirituality, and land stewardship into a coherent whole. Hawaiian sovereignty was not merely juridical; it was cosmic. Authority flowed from genealogical legitimacy, divine responsibility, and reciprocal obligation between ruler, land, and people. This system, while unfamiliar to Western industrial states, was internally stable, sophisticated, and internationally recognized throughout the nineteenth century.

The Fracture of Alignment

By the time Liliʻuokalani ascended the throne in 1891, the Hawaiian Kingdom had already been destabilized by foreign economic interests-principally American and European sugar planters-whose wealth depended on political leverage rather than lawful sovereignty. The infamous Bayonet Constitution of 1887, imposed under duress upon her predecessor, King Kalākaua, had already stripped the monarchy of meaningful executive authority and disenfranchised native Hawaiians.

Liliʻuokalani’s reign must therefore be understood not as a period of decline, but as a corrective attempt-an effort to realign the political structure of Hawaiʻi with its ancestral, constitutional, and moral foundations. Her proposed constitution sought to restore suffrage to her people and return governance to its rightful custodians. In doing so, she challenged not only local oligarchs, but the broader imperial logic that assumed indigenous sovereignty to be negotiable.

Her overthrow in 1893 was not the result of popular revolt, nor of internal collapse. It was a calculated seizure of power, executed by a small group of foreign businessmen with the backing-implicit and explicit-of U.S. military forces. This act represents a textbook case of political dissonance: where legality, legitimacy, and force were deliberately uncoupled.

Detention, Dignity, and Intellectual Resistance

Following a failed counter-revolution by royalists, Liliʻuokalani was arrested and placed under house detention at ʻIolani Palace-her own royal residence. It was during this confinement that she authored Hawaiʻi’s Story by Hawaiʻi’s Queen, a work of remarkable restraint, clarity, and moral authority.

Here, Liliʻuokalani emerges not merely as a deposed ruler, but as a philosopher of sovereignty. She refused to sanction violence that would endanger her people, even when restoration of her throne might have been possible through bloodshed. This decision, often misinterpreted as weakness, reveals instead a higher political ethic-one that placed collective survival above personal power.

From an Atomic Re-Alignment perspective, her restraint represents a refusal to fracture the social nucleus of her civilization. Where colonial regimes relied on disruption, extraction, and fragmentation, Liliʻuokalani chose coherence, memory, and continuity.

Marriage, Lineage, and the Politics of Isolation

Her marriage to John Owen Dominis, a man of foreign descent, has often been portrayed as a political liability. Yet the deeper tragedy lies not in the marriage itself, but in the structural isolation imposed upon her by colonial power. Without direct heirs and increasingly marginalized within her own kingdom, Liliʻuokalani became symbolically singular-a lone custodian of a sovereign lineage under siege.

This isolation mirrors a recurring pattern in colonial history: the neutralization of indigenous authority through genealogical interruption, legal displacement, and narrative erasure. The monarch is preserved as a figurehead while sovereignty is quietly transferred elsewhere.

Legacy and Re-Alignment

Liliʻuokalani died in 1917 in Honolulu, her kingdom formally annexed, her authority unrecognized by the very powers that had once acknowledged it. Yet history has not resolved in favor of her usurpers.

In the late twentieth century, the United States formally acknowledged its role in the illegal overthrow of the Hawaiian Kingdom. While symbolic, this admission confirms what Liliʻuokalani asserted all along: that sovereignty cannot be extinguished by force without creating long-term instability.

From an IoBN perspective, Queen Liliʻuokalani represents a critical case study in ontological and political misalignment-where the displacement of legitimate authority produces enduring cultural, legal, and psychological fractures. Her life reminds us that power divorced from moral legitimacy is inherently unstable, and that civilizations, like atoms, cannot be forcibly rearranged without consequence.

Conclusion

Queen Liliʻuokalani was not simply the last monarch of Hawaiʻi; she was a guardian of civilizational integrity at the moment of its greatest peril. Her legacy endures as a testament to dignity under duress, sovereignty without violence, and resistance through memory and truth.

In an era still grappling with the aftershocks of imperial disruption, her life stands as a call for re-alignment - not backward into nostalgia, but forward into a more honest reckoning with history, power, and legitimacy.

She did not lose her kingdom.

It was taken.

And the imbalance remains.