posted 16th December 2025

The Black Saint, the Crown, and the Forgotten Architecture of Power

Reclaiming African Imperial Authority in European Sacred Art

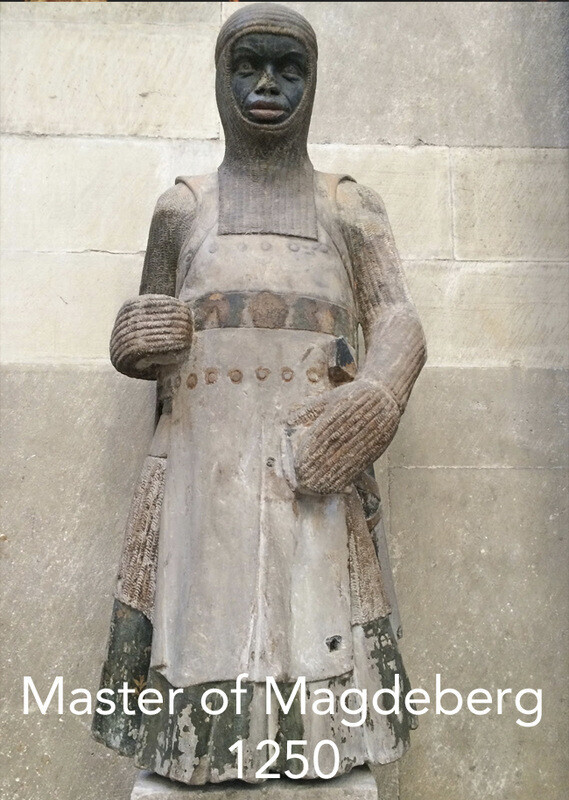

Across the cathedrals, palaces, and sacred collections of Europe exists a body of art that modern audiences often encounter with confusion, disbelief, or silence. Among these works are striking depictions of Black African figures—crowned, armoured, enthroned—standing not at the margins of civilisation, but at its very centre. One such image, reproduced and venerated across medieval and Renaissance Europe, depicts a Black kingly warrior-saint bearing the insignia of imperial authority.

This figure is not an anomaly, nor a symbolic abstraction. He represents a historical and theological reality long acknowledged by European institutions and later obscured by racial revisionism. Traditionally identified as Saint Maurice, this image opens a critical window into the suppressed architecture of power, nobility, and legitimacy within early Christianity and the Roman world.

The Artistic Tradition: Africa at the Heart of European Sacred Imagery

The figure belongs to a well-established Late Roman, medieval, and Renaissance artistic tradition, particularly prominent in Germany, France, Switzerland, and Italy. Saint Maurice—Mauritius in Latin—was revered as a high-ranking Roman military commander from Roman North Africa, traditionally associated with the Theban Legion.

From the 4th century onward, Maurice was venerated as:

A Roman officer of elite rank

A Christian martyr

A protector of emperors and soldiers

A symbol of moral authority over raw power

Crucially, European artists did not shy away from his Africanness. He is consistently portrayed with dark skin, African features, Roman armour, and, in many cases, royal or imperial regalia. These depictions were commissioned by emperors, princes, cathedral chapters, and military orders—not radicals, not outsiders, but the custodians of European legitimacy itself.

Why the Crown Matters: Authority, Not Allegory

Modern viewers often misinterpret the crown as metaphorical or decorative. In medieval and Renaissance visual language, this is a grave misunderstanding.

The crown in such imagery signifies imperial authority under divine sanction. It does not denote a local European kingship, but rather continuity with Roman imperium—a universal authority believed to transcend ethnicity, geography, and later racial categories.

Holy Roman Emperors, in particular, deliberately associated themselves with Saint Maurice to assert:

Their inheritance of Roman legitimacy

Their continuity with early Christianity

Their submission to a moral authority that predated medieval Europe itself

In short, the Black saint was not crowned despite Europe—he was crowned before it, and therefore above it.

Historical Reality: Africa and the Roman-Christian World

This iconography aligns with historical fact.

Roman North Africa was not peripheral. It was:

One of Rome’s wealthiest and most strategic regions

A centre of military recruitment

A cradle of Christian theology and law

Africa produced:

Emperors, including Septimius Severus

Generals and governors

Senators and jurists

Popes and Church Fathers

Christianity itself spread first through Africa and the Eastern Mediterranean. Europe was a recipient, not an originator. Early Christian authority—intellectual, theological, and administrative—was African and Levantine long before it was Northern European.

Thus, when Renaissance artists painted Black saints crowned and armoured, they were not inventing diversity. They were preserving memory.

The Later Erasure: From Acknowledgement to Amnesia

The discomfort surrounding these images is not medieval—it is modern.

From the 17th to 19th centuries, as racial hierarchies hardened under colonial ideology, Europe began to reinterpret its own past. African authority within Roman and Christian history became inconvenient. Black saints were reclassified as “exceptions,” their Africanness downplayed, spiritualised, or ignored altogether.

Yet the art endured.

Stone statues in cathedrals, illuminated manuscripts, altar panels, and imperial seals continued to testify to a truth that ideology could not fully erase: African nobility was foundational, not peripheral, to European civilisation.

Why This Matters Now

For the Institute of Black Nobility, this image is not merely historical—it is instructional.

It demonstrates that:

Black nobility is not revisionism, but restoration

European institutions once openly acknowledged African imperial lineage

Erasure followed power shifts, not evidence

Authority, knowledge, and civilisation have always been multi-civilisational

In reclaiming these truths, we do not seek to diminish Europe, but to liberate it from historical dishonesty. Only through accurate memory can genuine unity, scholarship, and human dignity emerge.

The Crown Remains

The crowned Black saint stands as a silent but enduring witness. He does not argue. He does not apologise. He simply is—armoured in history, crowned in legitimacy, and placed by Europe itself at the altar of power.

To see him clearly is not to rewrite history.

It is to finally read it without fear.